23-01-2022

Jimmie Durham: A Gatherer of Worlds

He had several lives, and traveled the world as a gatherer.

Jimmie Durham 2019; (c) Maria-Thereza Alves

He had several lives, and traveled the world as a gatherer. He left behind works of art that get under the skin of our civilization. The international art scene recognized his original power and honored him accordingly. The sculptor and activist was often attacked in Native North America because of his origins, but he never let himself be swayed by these attacks. On November 17, Jimmie Durham, 81 years old, died in Berlin.

A personal tribute to his life by Claus Biegert.

Winter 1973 in South Dakota. Native Americans and U.S. forces face off on the Pine Ridge reservation. Wounded Knee, site of the last massacre in 1890, is occupied. Members of the American Indian Movement, at the request of the traditional Lakota, have staged the takeover to raise issues of racism, corruption, persecution and land theft. Washington sends in the military and FBI. A turning point that unites Native American peoples like no event before.

Spring 1973 in Switzerland. Not far from Lake Geneva, a young man, 33 years old, walks broodingly. He has been studying at the “Ecole des Beaux Arts” in Geneva for four years, he comes from Arkansas, loves traveling, has an indigenous background, his parents were Cherokee, in the ancestry there were Scots and French. The Cherokee were never racists, always open to immigrants, so light skin is not a flaw. The hiker’s name is Jimmie Durham. Before he starts on his way home that day, he sees a roadkill badger lying beside the road. Artists look at found objects with artists’ eyes, wanting to breathe new life into them in their creations. He skins the animal and cuts off the head. As he handles the fur and skull, the message he receives from the dead animal is: Go home! Jimmie feels it with every fiber. A few days later, he books a flight across the Atlantic.

Why had he left North America in the first place? In 1975, I was able to ask him this question in New York City. This was his answer: “I went to Europe mainly to look around and to get to know the homeland of the white people. I left America because it was shortly after the occupation of Alcatraz Island* and I felt that we Native Americans were just too torn apart and confused to get anything going. Also, I didn’t want to be in the U.S. anymore; when the news came on the radio that Martin Luther King had been assassinated, my work colleagues clapped. And then I thought to myself, I have a light skin, why don’t I try to escape everything here and live a comfortable life among white people as an artist. So I went to Europe and it worked out pretty well at first. But suddenly it didn’t, I just couldn’t stop being Cherokee. And then came Wounded Knee in 1973. Everything in Switzerland spoke to me, the rocks and the badgers, everybody let me know I had to go back home.”

It was not only the badger, he admits, there was another little story:” I was in the south of France, in the Languedoc region, there I found a strange stone. It looked like a spider. I took the stone with me. Then I collected mushrooms, called crested pints, which I cooked and ate with a good red wine for dinner. Suddenly the stone turned into a dangerous spider, and I thought my life was coming to an end. I didn’t sleep all night, and in the morning the spider had become a stone again. I put the stone in my pocket and knew I had to go back. Many years later, I learned that these ink mushrooms develop a hallucinogenic effect when combined with alcohol.”

Wounded Knee was a rallying cry for all Turtle Island natives. “That same year I returned to the U.S. and from there I tried, as much as I could, to start European solidarity groups for our struggle. Because I felt that we had a base of solidarity in Europe, we didn’t find in our country.”

His intuition had not deceived him. The basis of solidarity exists to this day. Jimmie was welcomed with open arms upon his return to Switzerland, and together with activists on the ground and Enrique Manzo, Mapuche from Chile, and Tomas Conde, Aymara from Bolivia, he founded the initiative “Incomindios” in 1974, which remains a pillar of European indigenous support work to this day. More or less at the same time, he took over the leadership of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) in New York, in order to cast an anchor from there into the European arena of international politics, to the UN in Geneva.

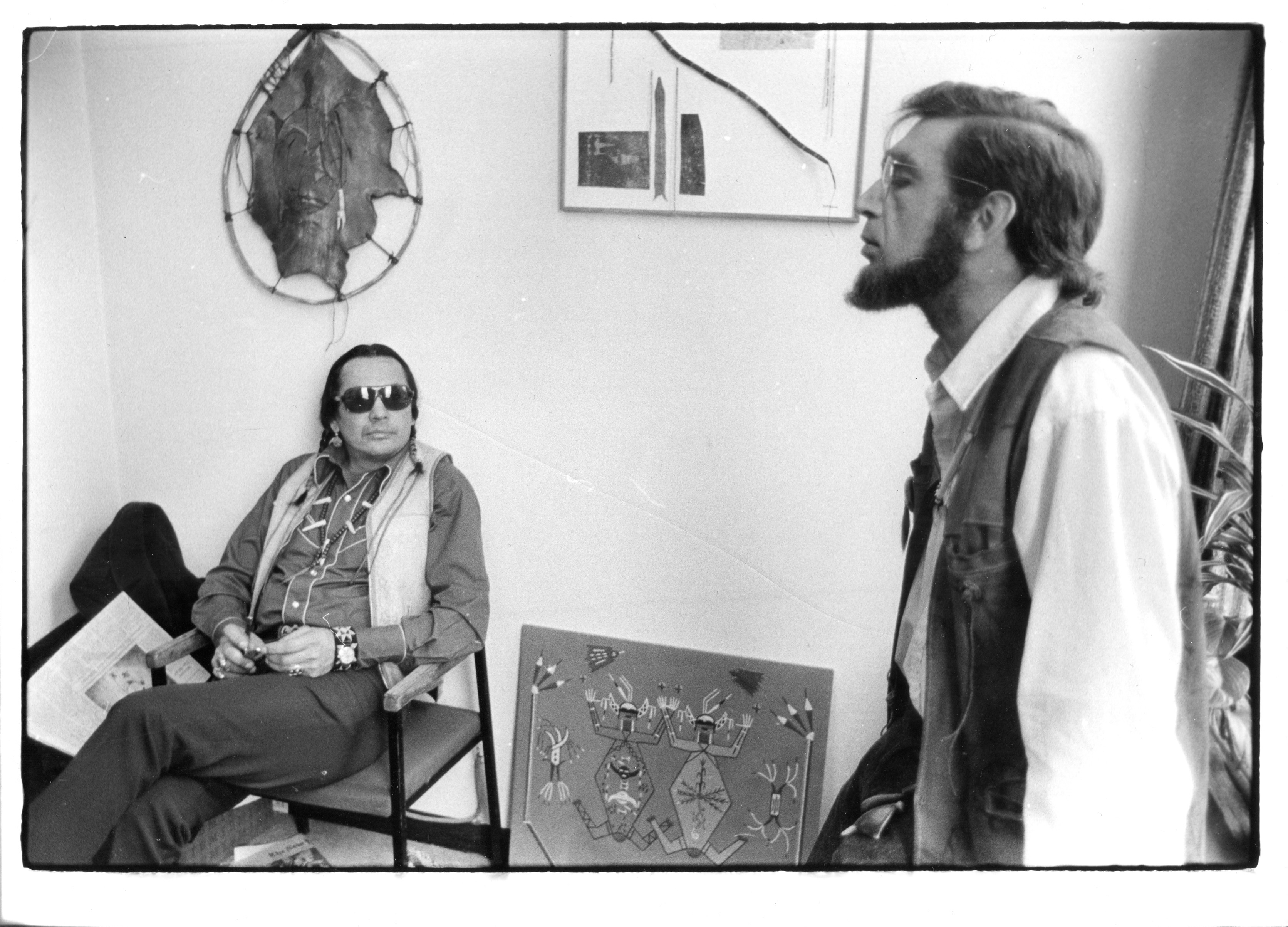

1975 the International Indian Treaty Council opened its office in New York City; In February 1976 Claus Biegert interviewed Jimmie Durham and Russell Means (left). (Photo: Claus Biegert)

A historic meeting – the First International Indian Treaty Conference – on the Standing Rock reservation in South Dakota in June 1974 had preceded it: The American Indian Movement convened an historical meeting – the First International Treaty Conference – that brought together over 4,000 indigenous representatives from 98 nations across the Americas and the Pacific. Jimmy was designated to establish a headquarter in New York City. An office across the street from the UN was given to the Treaty Council by the World Council of Churches – and Jimmie took the helm as the founding director. It was there that I met him for the first time. I had already heard of him because my school friend Hans Angerer from Murnau also studied at the “Ecole des Beaux Arts” and often told me about his conversations with Jimmie.

When the IITC was looking for a logo, Jimmie went to New York’s Westside, to 89th Street. There lived illustrator Richard Erdoes, immigrant from Austria and prominent supporter of the American Indian Movement; he even spoke a limited Lakota. Erdoes had risen to prominence in the Native world (and in ethnology) after Lakota medicine man Takha Ushte (John Fire Lame Deer) persuaded him to publish his, Lame Deer’s, biography. “Seeker of Visions” became a best-seller – it was the first time a Native American had used a “white man” to tell his story.

To him Jimmie went, and Richard said tomorrow he could pick up the logo. I happened to be a witness; that afternoon I had an interview scheduled with Richard. No time, Richard said, and I got to look over his shoulder for it, as he slanted a pipe through the double continent, making it clear that the radius of the IITC would extend beyond the US. The whole thing was held up by a circle – globe and seal in one. To this day, the Treaty Council logo signals the unity of the Indigenous Americas.

IITC-LOGO

Two years later, the bags were packed for Switzerland, from Alaska to Amazonia, tribal leaders, clan mothers, activists gathered their papers, their families, their best clothes and flew to Switzerland in September 1977. For two years, Jimmie Durham had shuttled between Geneva and New York City to prepare for the meeting with ECOSOC (Economic and Social Council), acting as a messenger between worlds, gathering wishes and documents, laying the groundwork for a gathering of historic proportions. In early September, he flew back to New York, staying away from the week-long conference at the UN in Geneva. He had done his job, he told me, and wanted to stay in the background, not taking a place that would be missed by the main people at the conference, for example Winona LaDuke: the young Harvard student saw in him a role model and had chosen the activist path; in front of the UN that September, she was the youngest speaker. Her issue: uranium mining on reservation land.

1975 the International Indian Treaty Council opened its office in New York City; Jimmie Durham worked closely with AIM-leader Russell Means (left) Photo: Claus Biegert

At the end of the seventies, the artist and human rights activist Durham again gave more space to the artist. He collected objects in many places, put them together contrary to their previous order, wrote poems, mixed his texts with the transformed objects, became a wanderer, a world collector; he was joined by the Brazilian video artist Maria-Thereza Alves, whom he had met in the environment of the Treaty Council. Maria-Thereza gathered the necessary knowledge at the Treaty Council to launch a similar initiative in Brazil. In 1987 they both went to Cuernavaca in Mexico, and in 1994 to Europe, first Marseille, then Berlin, and later Naples.

In 2002 I visited him in Berlin, he had a large studio in Seelendorf, the action artist and Fluxus founder Wolf Vostell had used it for 25 years before him, originally it had been built for Adolf Hitler’s favorite sculptor Arno Breeker. Jimmie had been part of the international art scene since he was represented at documenta IX in Kassel in 1992. He never fulfilled the expectations he met there. He didn’t want to be an Indian artist, he said, just a Cherokee who makes things. But even this modest attitude was to be held against him as his fame grew.

Artist, activist, or is he both? “I don’t think I’m an artist or an activist, I don’t think in those categories. I started my career as a cowboy, because I was good with horses. Then I went into the military. At that time I could have called myself a murderer. But neither cowboy nor murderer suited me as a career. In the early sixties, I joined a black theater group. I wrote poetry and and produced what has come to be called performance art. I wasn’t doing visual art, I was doing theater and poetry, but I would never have called myself a poet, that would have sounded boastful to my ears. Then I got invited to do exhibitions, and I just kept on making things. It’s my life.”

Indigenous maker of things, maker of things with an Indigenous background , or just sculptor and writer? “When I do work as a sculptor or write poetry, of course I do it as Cherokee, but it doesn’t mean at the same time that you can tell the work is Cherokee. Because if my stuff looked like typical Cherokee stuff, then I would just be copying Cherokee stuff. I think of this wonderful old man: Mario Merz. His ancestors came from Switzerland, but he’s Italian, a more wonderful artist with a lot of strength in him. He is an Italian artist through and through. But that doesn’t mean he produces Italian art, it simply means that he makes art as an Italian.”

Some time later he adds, “In 1974 we were in Lincoln, Nebraska at the Wounded Knee trials. Whenever I found time, I would do little things in my room: pen and ink drawings, collages on paper and on fabric. And then Roger Iron Cloud knocked one time and said, ‘You always go to your room and do your stuff, why don’t you show it to us? Why are you so selfish and hide them? Why don’t you bring them to the big room where we work?’ Then he took some and hung them up, and I finally gave him all of them. I was so happy. I felt useful with my things.”

The 1973 Swiss badger skin is suddenly in our conversation, “When I was unexpectedly invited to documenta IX, I took the fur to Kassel in 1992 and made an outdoor piece with it. After almost twenty years, the badger skin was back in Europe, where it came from. I left it in Kassel.”

Animals make their appearance again and again in his works. He collaged reality and connected things that did not belong together, opening our eyes to a world that is out of joint and where connections are torn apart because we have overstepped our boundaries. Archaic bull skulls on furniture, bear bodies on sewer pipes: By force we bring nature into our artificial world, by force nature will one day respond. This day of revenge is present in each of his installations. They are signals of remembering in a time of forgetting, of pausing in a time of hurrying. And for Durham, the violence with which humans appropriate other beings without understanding them is akin to the mercilessness of the continued genocide of indigenous peoples. “When I read that Venzuela wants to give land to the Yanomami, I have to say that the state of Venezuele doesn’t even have land to give to the Yanomami. The Yanomami alone have land that they could give to Venezuela or Brazil. It is always a question of consideration and a question of power. We indigenous people in the two Americas are not considered people with rights. What do they even concede to us? Probably only feathers.”

Durham combines these feathers into a showcase with, for example, fictitious artifacts, which are supposed to be given supposed authenticity and historical significance by the title “On Loan…”. Of course, “real” arrowheads or “scalp hairs” may not be missing, and as a special addition, the showcase is adorned with a blood-red handprint of the artist – designated as “Real Indian Blood”.

In the Neolithic we sat at the fire and threw the gnawed bones behind us; behind us they were still food for others, finally they fertilized the soil. And the cycle began anew. All at once they were no longer bones, even if the movement remained the same: in a high arc far away what we can no longer use! Behind us are mountains of plastic on contaminated soil, floating on contaminated waves, or more precisely, we are already sitting on it, because the space behind us no longer absorbs anything. It is also the world of garbage in which the man-of-the-matter pokes.

The Durham-Alves community was a remarkable artistic duet: two brilliant, creative minds give each other impetus, cooperate, shuttle apart, collide again, emerge in each other’s work, complement each other, challenge each other. Jimmie and Maria-Thereza were a duo that played ping-pong with impulses and ideas, while Maria-Thereza as a filmmaker provided moving images. Always, both of them always turned back to their own productions.

Common to both: to turn our usual view of things upside down; in focus for both: post-colonial traces. After all, we move in a world whose raw materials, goods, buildings, products are the result of plundering – and we are children of a pirate civilization. Maria Thereza’s interdisciplinary work “Seeds of Change” should be highlighted here as representative of her oeuvre: she examined foreign soil for foreign seeds. European and American ships in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries had loaded soil and debris as ballast when they returned empty to their home port after transporting slaves from overseas. The ballast was then unloaded near the port. This overburden from distant lands (be it New York City, be it Liverpool) housed unknown seeds: Witnesses of cruelty. To these seeds she gave visibility, using them to create a flora of colonialism and early globalization.

Jimmie’s honors show that his visual language was understood: After the solo exhibition at MOMA in New York came the invitation to Documenta IX in 1992 , followed by doCUMENTA 13 twenty years later, when he planted an Arkansas Black Apple in the former orchard of the Karlsaue state park a few months earlier. In between there was also a professorship in Malmö. In 2016, the jury of the Goslaer Kaiserring decided in his favor. The Kaiserring has been awarded since 1975 (Henry Moore was the first laurate) and is considered one of the most prestigious art prizes in the world. Durham was often present at the Venice Biennale, or its surroundings; in 2019 he was awarded the Golden Lion there for his life’s work. Exhibitions were held throughout Europe and eventually again in the U.S., Hammer in Los Angeles, Whitney in New York, The Walker in Minneapolis.

With fame came reproach and protests; critical observers interpreted them as envy. Cherokee Nation tribal governments and various Cherokee artists went on record saying Durham had no right to call himself a Cherokee, that his name could not be found in any Cherokee registry. True, Jimmie said, his family had evaded registration.

The so-called Tribal Roll dates back to the General Allotment Act of 1887, which recorded tribal members and parceled out remaining Indian land on a per capita basis, driving its shrinkage. It was a colonial instrument, not an allocation of any kind of sovereignty. Tribal lands were to be turned into private lands, but private ownership was alien to indigenous societies. Those who rejected the colonial system of registration were punished by not being listed.

The pan-Indian newspaper Indian Country Today published the Cherokee critics’ open letter in June 2017. It was headlined. “Dear Unsuspecting Public: Jimmie Durham is a Trickster.” I can imagine how Jimmie must have laughed when he read that. Trickster, that’s exactly what he was: the tribal clown, the court jester, the free spirit who holds up a mirror to us, who takes aim at our behavior. Among the Lakota, the trickster is called Heyoka, translated: the hot-cold one, the forward-backward one, the one who mounts the horse backwards and holds on to the tail. It is part of the trickster’s nature not to be pigeonholed.

The Goslar jury recognized his trickster nature when it judged in 2016 that he “cannot be assigned to any artistic movement, but transcends all existing classifications. Following his permanent demand for freedom, the artist always strives to escape any hierarchical system.” On this, quote Jimmie Durham: “If architecture preaches the linear, then I work against the linear. If architecture praises the stone as a foundation, then in response I pick up a stone from the ground and throw it.” When he learned that the stone blocks ordered by Hitler in Sweden for Albert Speer’s triumphal arch for the capital, “Germania,” were still lying there in the quarry, he wanted to buy them and have them sunk into the Baltic Sea so that new life would grow on them, but he couldn’t find any financial support for his plan. “Maybe it’s part of me to always do the opposite, to turn things around, to deliver the unexpected.” If that’s not a trickster’s confession! “I made two Triumph Arches for personal use. One is metal and has two wheels. You can fold it up and rebuild it if you have a moment of triumph. One can march through and whistle a song. The other one is made of wood and also folds up. It doesn’t need wheels, you can put it on your shoulder. I’m more interested in movement than monuments.”

The gatherer of worlds and man-who-makes-things world collector was also a writer, a gatherer of words, 13 booklets are filled with stories, poems and essays, valued among art lovers, but little known outside their circle. “Columbus Day” (1983), “A Certain Lack of Coherence” (1993), “Poems That Do Not Go Together”(2012), “Social Medium: Artists Writing, 2000 – 2015″ (2017). They came alone or accompanied exhibitions. In his latest opus ” God’s

Children, God’s Poems” he addresses our treatment of wildlife and concludes, “as it stands now, it will take the earth millions of years to get rid of our footprints.”

In 2012, Jimmie and Maria-Thereza created themselves a studio out of a factory space in Old Naples. In the kitchen area hangs a framed, handwritten statement on the wall, HUMANITY IS NOT A COMPLETED PROJECT. Humanity: isn’t it the great interdisciplinary project that Jimmie and Maria-Thereza collaborated on?

*Alcatraz Prison Island off the coast of San Francisco was occupied from November 1969 to June 1971 by indigenous activists who called themselves “Indians of All Tribes.”

Tlunhdatse, 1985, mixed media - a typical installation by Jimmie Durham Photo courtesy: Nicole Klagsbrun

SHARE