16-06-2021

CROW DOG: A MEDICINEMAN CHANGES WORLDS

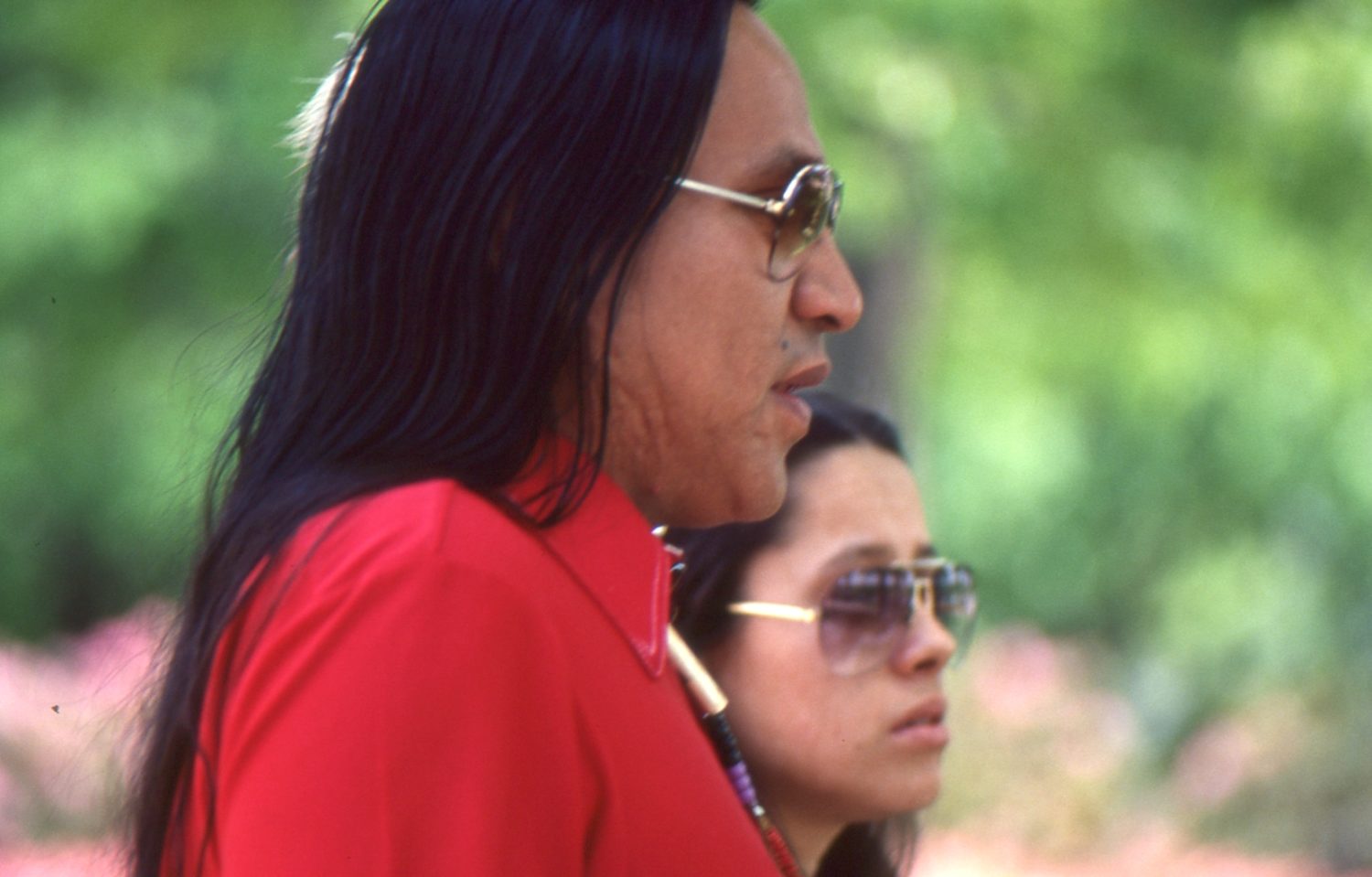

Foto: Christian von Alvensleben

Leonard Crow Dog of the Brule-Lakota Nation on the Rosebud Reservation, South Dakota embodied the spiritual power of the American Indian Movement – and was persecuted for it. He died June 6, at age 79.

An obituary by Claus Biegert

We all got to see Leonard Crow Dog in a wheelchair on YouTube, listening to veteran Wesley Clark Jr. during the Standing Rock uprising. Clark Jr. was asking for forgiveness that his people, his ancestors, had stolen Native lands, as well as their children, their cultures. It was Dec. 4, 2016, and Clark, the son of a NATO general, had led a nationwide delegation of veterans to Standing Rock to offer solidarity and protection to the Dakota Access Pipeline resistance camp. Crow Dog placed his hand on the head of the man kneeling before him and spoke words of forgiveness. Then he asked for a microphone. “We do not own the land,” he said, “the land owns us.” He ended his speech with a call for peace in the world. A tearful healing ceremony followed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hx3K6ZZuIys

Leonard Crow Dog came from a line of Brulé Lakota medicine men that goes back four generations. He was born in February 1942 on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. His parents, Mary Gertrude and Henry Crow Dog, because he showed special transcendental abilities at an early age, decided not to send him to school. It is a testament to the respect the family enjoyed that the tribal government tolerated such a decision. Leonard instead apprenticed with four different medicine men. When asked about this, he always said, “I went to the university of the universe”. Learning English along the way, he spoke and thought in Lakota. His English vocabulary was distinguished by personal word creations and poetic puns.

At the February 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, he was there from the beginning, his job to provide ceremonies and care for the sick. As the army tanks rolled up, Crow Dog marked the faces of the AIM warriors with red paint; he knew it was serious, he wanted to tell them that “it’s a good day to die.” Leonard was accompanied by his wife Mary, who gave birth to their son Pedro during the siege.

The pan-Indian newspaper Akwesasne Notes reported a physician, Dr.Cowan from Seattle, Washington, who helped out during a week at Wounded Knee and had considered it an honor to work alongside Leonard Crow Dog. Cowan witnessed him treat two gunshot wounds with herbs that were analgesic and antiseptic, but whose pharmacological significance he did not know, only the names in Lakota. Crow Dog: “I had my spiritual power, my sacred plants, and my pocket knife.” Dr. Cowan: ” At first I thought all these spiritual things were silly. Now I know that prayers and ritual preparation are as important as the substances themselves.”

One day, four armed FBI agents disguised as postal workers managed to slip inside through the ring of Native guards. The hoax was soon busted. Several young AIM men disarmed the informers and brought them into the small tourist museum next to the Trading Post. Leonard Crow Dog, who was in the museum at that very moment, took the opportunity to give them a lesson on the sovereignty of the “Independent Oglala Nation” that the squatters had proclaimed and the triggers of this indigenous resistance. Then he escorted the four back to the police belt.

That was enough for the state apparatus to charge him with “inciting violence and obstructing federal officers from performing their duties.”

The trial was held in June 1975 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa; it lasted three days. The defense was not allowed to ask questions of the jury. The witnesses called – three of the the four “postal workers” – were unable to identify Crow Dog, contradicted each other, and admitted under questioning by the defense that they had not been assaulted or harassed. The sentence was 11 years. The mountain of petitions on Judge McManus’ desk may have contributed to the suspended sentence. Among the senders, mostly churchmen and artists, was Marlon Brando.

But Crow Dog was not to get any rest: On September 3, 1975, two men came onto the property at night and were held by the guards. Since the house had been repeatedly shot at since Wounded Knee, friends and relatives took turns keeping an eye on the houses. A scuffle ensued and the intruders took off without Crow Dog catching sight of them. It later turned out they were two convicts named McCloskey and Beck.

Two days later, it was three o’clock in the morning, uninvited guests arrived again: 120 federal police and FBI agents – in helicopters, on rubber boats (a creek runs through Crow Dog land) and armored cars, with spotlights and machine guns, dressed in combat vests. They chanted, “We’re gonna take to jail and you’re gonna stay there forever,” they tore his elderly mother’s bedding, they threw his two-year-old son Pedro out of bed and held a gun to his wife’s temple when she tried to intervene. They tied Leonard naked by his hands and feet and suggested to ran him through a gauntlet.

Finally, they put the handcuffed man in a wagon and transported him to the county jail 90 miles away in Pierre, the capital of South Dakota. There they woke him every hour, tugged at his long hair, and asked him the whereabouts of Dennis Banks. (The latter was wanted nationwide, having gone into hiding after William Janklow, governor of South Dakota, suggested a bullet through Banks’ head as a solution to the Indian problem. Popular at the time was a T-shirt that read “I am not Dennis Banks.” Banks was arrested in San Francisco in January 1976 and granted political asylum by California Governor Jerry Brown.)

The charge was “assault with bodily injury,” and the trial in Pierre had been scheduled so close that the defense attorneys had no time to prepare. The sentence was “two five-year terms” for being responsible for all that happened on his property.

The Terre Haute penitentiary in the state of Indiana was the first stop of the twice five years. In a single cell without windows, 1.20 x 2.10 meters and 1.70 meters high, he spent three weeks without interruption and without physical activity. This, the prison authorities assured him, was not punishment, since Terre Haute was not yet his final prison, he was not entitled to a normal cell.

On January 5, 1976, he was suddenly transferred to Rapid City, South Dakota. Richard Erdoes, an illustrator and writer from New York (originally from Vienna) and close family friend visited him in the Rapid City County Jail five days later. “I found,” he told me, “a man completely degraded physically. He had lost 40 pounds, his skin had turned pale, his hair still showed traces of the ordeal.” Erdoes was shocked by the composition of the 60 jail inmates: 56 Native, 4 black.

Crow Dog had been moved to Rapid City because of an incident for which the trial was still pending: On March 25, 1975, Mary and Leonard had returned from grocery shopping in Rapid City and found three men unknown to them in their house. One of the three introduced himself as Roger Pfersick and pretended that a beckoning from the Great Spirit had led them here. Mary and Leonard invited the strangers to stay for dinner. After dinner, Pfersick grabbed Mary, trying to get under her skirt; Leonard instructed the guests to leave. “You don’t have to order me around at all,” Pfersick yelled at him, “this is a free country and I can do what I want.” Pfersick swung at Crow Dog, splitting his lip. I got these details from Richard Erdoes.

The indictment on this talked about a “threat with a dangerous weapon.” Leonard had threatened Pfersick with a tomahawk. When the defense argued that it was a plastic toy, the prosecutor replied that even a soft noodle is a dangerous weapon if it is used with the intent to kill.

The trial lasted two days; all jurors were white. A color photo showing prosecutor Pfersick bleeding turned out to be fake: the blood had been applied after the fact. Roger Pfersick, as a prosecution witness, appeared in a suit with a star-spangled tie, in contrast to his appearance at Crow Dog’s house.

Federal prosecutor Hurd gave an introductory taste of his ethos: “Ladies and gentlemen, this country, this government and its system are good … protecting them is one of my jobs. In doing so, I am also protecting you, ladies and gentlemen … Roger Pfersick is alleged to have molested Crow Dog’s wife, rather I believe he was kicked out of the house because he was a government informant. And if he was indeed a government informant, it was to protect you and the system, ladies and gentlemen.”

Richard Erdoes, who took notes of the statements, expected the worst; but then the sentence was added to the previous sentence without any increase in the term of imprisonment. The pronouncement of this surprising sentence took place in Richmond, Virginia, where Leonard had since been transferred. It was the fourteenth prison. Amnesty International Sweden had adopted the medicine man in the meantime.

In early 1977 Crow Dog regained his freedom; the international interventions of human rights organizations had not been in vain. In April I traveled for the magazine “stern” together with the photographer Christian von Alvensleben through Indian America between Massachusetts and Arizona. In Washington, Richard Erdoes joined us and we accompanied the Crow Dogs (Mary and Pedro and a sister of Leonard’s had also come) to the BIA and the National Council of American Indians. When we parted, Leonard invited us to Crow Dog’s Paradise (Henry had given this name to the place), for the first peyote session after his release. We promised to come.

https://alvensleben.com/stories/cva_native_americans_1977.html

The day before the peyote ritual, the ceremonial tipi was erected. Christian documented every step. When all the poles were in place, a flock of songbirds flew between the tops. “It’s a good sign,” Crow Dog said, “when the tipi is up, the birds come.” Leonard’s parents helped prepare the hospitality for the guests. During the day there were clear skies overhead, dark cloud banks on the horizon around us. When the first visitors arrived, the clouds above us gathered into a gray blanket, the horizon was bright and cloudless in all directions. Many flashes of thin lightning descended on our place without much thunder being heard. We walked through them as if those were already part of the ceremony. That night, through the impact of the peyote cactus, I learned what Crow Dog meant when he spoke of his cousin, the tree, or referred to the rock as brother and the fire as grandfather. I suddenly felt a close kinship to the landscape around me and to the trees and plants.

Richard Erdoes had known Leonard since childhood. He told us how the latter had held a Ghost Dance on his land in 1974. Those who danced the Ghost Dance, it was said in the late 19th century, would help the land recover and the bisons and Native Americans return. The dance was banned by the U.S. government because it was seen as a call to war. Leonard wanted to reintroduce the Ghost Dance. He had the dancers sew shirts for themselves – Ghost Dance shirts – and danced with them for several days. Richard Erdoes took photographs at Leonard’s request, and a friend filmed. On the third day of the dance the eagles came, I could see it in the film. It was an unusual sight: The eagles flew in a wedge formation, as only geese usually do. For Crow Dog, it was confirmation from the spiritual world, the world he was in constant communication with.

Leonard Crow Dog was a medicine man and activist in one, a union of spiritual power and political resistance. That’s why he went to Standing Rock to receive the veterans. That’s why he went in the eighties to Big Mountain and held a Sun Dance to support Hopi and Navajo in their struggle against an unwanted government fencing. Time and again, he raised his voice for Leonard Peltier. When the news came, that Leonard Crow Dog had gone to the Spirit World, the Rosebud Tribal Council set the red and white tribal flag with the twenty tipis at half mast.

SHARE