11-06-2024

Window Rock, New York, Innsbruck

Spring travel writings by Claus Biegert

The Pueblo actor Joe Runningfox belongs to the staff of the TV series DARKWINDS, based on the novels by Tony Hillerman

It is early in March 2024, I am accompanied by Eda Gordon, who picked me up at the Sunport in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In fact, I’m her companion, because we’re in her car and she’s behind the steering wheel. We are heading west on Interstate 40 towards Arizona. As a documentary filmmaker, I am invited to the Uranium Film Festival at Window Rock, the Navajo Nation’s seat of government, which extends in single-storey buildings below a rock with a round window – Window Rock.

The Navajo are a large indigenous tribe with over 300,000 people, whose reservation and habitat extends across the four US states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Colorado. But here’s a correction: They call themselves Diné (the people) and their land is Dinétah, framed by four sacred mountains: Sis Naajiní (Blanca Peak), the “Mountain of the White Shell Range” in Colorado, Dootł’izhii Dził (Mount Taylor), the “Turquoise Mountain” in New Mexico, Dookʼoʼoosłííd (San Francisco Peaks) in Arizona, and Dibé Nitsaa (Hesperus Mountain) in Colorado.

Within the four sacred mountains immigrant settlers and multinational corporations have devastated the land and its resources, digging for coal and uranium.While coal mining is being phased out, they continue to mine uranium to this day, even though the Navajo Nation government has banned uranium mining since 2008 and has called for the restoration of over 500 abandoned mines on the reservation.

Defending their sacred mountains crystallizes the cultural discrepancy between our Western lifestyle and Hozho, the harmony that the Diné consider to be the basis for a fulfilled life. Hozho – a prerequisite for the interaction of all living beings – does not come about by itself: Harmony must be recognized, known and vitalized. Hozho requires daily care, a morning prayer of greeting to the mountains – both a perception of harmony with the non-human beings around us, as well as a perception of the lack of harmony and balance, a compassion with the plagued nature.

The Diné still use the name Navajo, given to them by the Spanish. It comes from a Tewa name, Navahuu, referring to their sedentary lifestyle tied to agriculture and raising livestock. The designations Navajo and Diné currently exist side by side, along with the generalized designation American Indian.

Interstate 40. Highway time is story time. Of course we talk about Leonard.

Eda is a freelance editor, private investigator and activist. We have both been involved for decades in the campaigns for the release of political prisoner Leonard Peltier.

The international solidarity movement had taken many paths, but even letters from Pope Francis to Presidents Obama and Biden had not led to his release. Leonard is still behind bars, 48 years already. It has been proven that he was not responsible for the deaths of two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Sioux reservation in South Dakota. However, he was present when a firefight erupted between the two FBI agents and members of the American Indian Movement protecting the Jumping Bull family compound in the village of Oglala. It was June 1975; the reservation was in civil war: Good Indians vs. Bad Indians. Traditional Lakota and American Indian Movement vs. Tribal Government and Bureau of Indian Affairs. The FBI targeted three AIM activists as the culprits. Dino Butler and Bob Robideau were acquitted on grounds of self-defense at trial. Leonard, who had escaped to Canada, was captured and prosecuted separately in a trial rife with government misconduct and constitutional violations. From 1974 to 1975 the FBI trained about 2000 special agents on the reservation. Eda had worked with the Wounded Knee Legal Defense/Offense Committee representing AIM during those years and had lived on the reservation during that time. “It was life-threatening,” she recalls.

We talk about Norman Brown. We both know him from our work. Norman is a Diné who has been active in the tribal initiative against uranium mining for decades. As a teenager, he joined the American Indian Movement. He was 15 and part of the AIM encampment, when the FBI agents were shot after driving onto the Jumping Bull compound on the Pine Ridge reservation. He and Leonard knew each other well, together they cared for the elderly and children. They shared a vision to counter control by the Bureau of Indian Affairs with a traditional model of tribal independence. Norman remembers June 26, 1975 to this day, and in his community work continues to envision a sovereignty rooted in traditional Dine values.

“I wonder if we’ll meet Norman,” I say as we approach Window Rock.

“Me too,” says Eda. “It would be so good to see him here.”

After almost three hours on the highway, we arrive at the Quality Inn in Window Rock. As we get out of our car in the almost empty parking lot, a man approaches us. His smile takes up his whole face. It’s Norman Brown. The three of us put our arms around each other, tears are wiped away.

Across the road is the Window Rock Museum, and for the second time it is the venue for the International Uranium Film Festival. The festival got its initial spark in Window Rock during an Indigenous Uranium Summit in 2006. Back then, visiting journalist Norbert Suchanek had traveled from Brazil and returned from the Summit to Rio de Janeiro with the intention of organizing a festival of topical films; he and his wife Márcia Gomes de Oliveira immediately set about implementing the plan.

Today, the Uranium Film Festival is an integral part of the international film festival scene and, through presenter/activist Libbe HaLevy, creator of the podcast “Nuclear Hotseat,” now also has a foothold in the USA. Window Rock opens a four-week festival tour through eleven states, with a detour across the Canadian border to Vancouver. After the annual festival in Rio in July, according to custom, the program goes on the road. A devoted financial partner has historically been the Seventh Generation Fund, whose director Chris Peters is also present at this year’s festival with his friends in wooly hats embroidered with: Be a good Ancestor.

The four-week “Turtle Island Marathon” begins with an early morning ceremony in a hogan, the traditional hexagonal Diné wooden house with an earth roof. This hogan stands opposite the entrance to the museum and is used exclusively for ritual purposes. Our friend Anna Rondon, who has been active in the resistance against uranium mining for decades, has asked Lawrence Begaye, a young medicine man, a Hataałii, to ask for the support and protection of those who have traveled long distances to attend the festival – support for their activism and protection from the power of the devastating stories we will hear in the films. Begaye comes from the nearby settlement of Black Hat in New Mexico and, like Anna, belongs to the Towering House Clan Kinya aa anni. Lawrence is bringing with him the aura of his famous teacher, John Holiday. Holiday was considered a legend during his lifetime because he could call the rain.

It is dark, we sit on the rammed earth floor, the fire crackles in the iron stove, the singing of the Hataałii carries us away. At the close of the ceremony, almost reluctantly, we leave the sheltered sacred space and step outside. It has started to snow. Gifts, addresses and hugs are exchanged, snowflakes all around us. The festival can begin. Thank you, Anna! Thank you, Lawrence Begaye!

Film and reality constantly touch each other. Just a moment ago, the view of a contaminated landscape on the screen, then lunch next to a woman who worked in a uranium mine. She is a widow; her late husband had worked in a uranium mine for decades. There is hardly a Diné family that does not have relatives who have fallen victim to uranium. There is hardly a family that did not get a job during the uranium boom of the 50s and 60s. Their medicine men and women were powerless to deal with the effects of the unknown radioactivity.

Without radioactive radiation, the picture is different: the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) have shown us that the indigenous peoples of the so-called New World can find their place in the expanding culture and growing economy of the 20th century and assert themselves there without giving up their own identity. It was the Mohawk men who comprised the construction crews hovering high in the air on bridge piers and skyscrapers. “Up there it’s just the creator and me”, an Onondaga high-steel worker told me. That’s how they all felt, he added. In the years when New York took on its current form, there were no safety ropes. As I walked across the Brooklyn Bridge with my daughter Tara in September 2023, I saw the Iroquois in my mind’s eye in the air, balancing, screwing, welding, tensioning. They had come with their families, lived in Brooklyn. When one troop went home, the next troop came and took over the apartment. Back on their reservations, they took care of the local needs; the good earnings on the construction sites spared them the fate of welfare recipients. High Steel became an integral part of Mohawk culture.

In Window Rock, I think of my Haudenosaunee friends who, despite their close proximity to white America, were able to preserve the core of their culture into the 21st century. For the Diné, the attempt to participate in the white capitalist economy ended disastrously.

Film festivals provide films talks. Lise Autogena, a filmmaker from Denmark working in Greenland, wants to know if I’ve seen “The Zone of Interest” yet. I haven’t been asked about a movie this often for a long time. An artifice had enlivened the cinema: the Höss family in private, and behind the garden walls the Nazi horror. Do we have to show the horrors? No! The side, the behind, the before and the after foreshadow the disaster and create a scenario in our minds that can no longer be extinguished.

In return, I bring “Oppenheimer” into the round. Thanks to the Oscars, the physicist is suddenly a household name. Robert Oppenheimer’s bomb was called Trinity. It was July 16, 1945, a Monday that changed the world. Whether the detonation would also ignite the earth’s atmosphere was the big question that engineers and scientists were asking themselves that spring. They quelled their doubts and set to work. The test was near Alamogordo in the White Sands desert, the land of the Apaches. Nobody lives there, the movie says, and that was the view of the nuclear establishment at the time. But today we know that around 40,000 people lived within a radius of 50 kilometers. To this day, they are not recognized as radiation victims. They were asleep in their homes on the edge of the White Sands desert when the Trinity bomb was detonated. The broken windows woke them up. Jimmy Carl Black, the drummer of Frank Zappa’s band Mothers of Invention, was living south of the test site in Anthony, a village in Texas near the New Mexico border. He later used the shards of glass that flew through his childhood bedroom in the lyrics of his music piece “Tumbleweed Canyon” on an album with the band Behind the Mirror, called “The Secrets of Crater 6.”

Christopher Nolan’s award-winning film conceals their misery. However, this concealment of the background is not a trick, but a method. Hollywood cements the nuclear empire. In Window Rock we are not far from the land of the Apaches, in a few hours we could be there, looking at the green glass residue of 1945. The heat of Trinity has given the desert sand a new shape.

First they bombed New Mexico, says Tina Cordova – first they bombed New Mexico. I met Tina a few months earlier when she was honored with the Nuclear Free Future Award in New York. In 2005 Tina had founded the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, an advocacy group for Trinity radiation victims. She is one of them, a cancer survivor who has lost family members to debilitating, deadly disease. Tina’s words ring in my ears again: “People die here on a regular basis, even four generations later. One child was recently diagnosed with eye cancer. We don’t ask if we will get cancer, we ask when.”

At the International Uranium Film Festival, outside the auditorium, Leona Morgan has set up an information stand with a map of the Grand Canyon behind her. Leona is a Diné social worker by profession who has dedicated herself for years to the resistance against uranium mining on her homeland. The Colorado River flows through the Grand Canyon and around 40 million people drink this water. The truck route for the mined uranium runs via the San Juan and the Little Colorado rivers. An accident would not just be a traffic accident. Leona vibrates when she speaks, her friendly eyes sparkle, it’s as if the canyon speaks through her. Grandmother Canyon is what the indigenous people call it. Now Grandmother is threatened by the Pinyon Plain Mine, not far from Red Butte, a sacred mountain of the Havasupai, which is also revered by the Diné and the Hopi. Leona is handing out a flyer. Written on it is “Defend the Sacred” and “Water is Life.” The flyer refers to this website: www.haulno.com

In our day and age, the sacred has little meaning. In the 1990s, the American social critic Jerry Mander published a book with the apt title “In the Absence of the Sacred.” For me, it was like a sentence that I had wanted to say for a long time but had not yet managed to formulate. When the sacred is absent, anything is possible. We have desecrated the earth in order to be able to exploit it without remorse. Klee Benally, the famous Diné musician and filmmaker, is quoted by many when talking about the sacred. It was Klee who introduced me to Leona many years ago. We all miss Klee. He died at the end of last year, aged 48. He left behind a book that seems like a call to us here, a call not to forget the earth: “No Spiritual Surrender – Indigenous Anarchy in Defense of the Sacred.” He has dedicated it to all those in despair – For you, who also

despairs – and published it as Creative Commons so that it can be distributed without further inquiry: anti-copyright, Klee Benally, 2023.

The Pinyon Plain Mine used to be called Canyon Mine. It was closed in 1992. However, if the Canadian company Energy Fels Inc. (EFI) has its way, it will be able to mine around 109,500 tons of uranium per year. Current approval is still pending, but the company is relying on a permit from 1986, which does not meet current requirements. The mine is located on land managed by the US Forest Service. So far the US Forest Service remains silent. In the absence of the sacred, anything is possible.

The German company Uranerz has merged with EFI. I remember an interview I conducted in the 1980s in Bonn (our capital at the time) with Rimbert Gatzweiler, the chief geologist at Uranerz. We were talking about Australia, where Uranerz had also acquired mining rights. I referred to the destruction of sacred places. His answer was

indignant: Suddenly the Aborigines would come, stand in front of the excavators and want to protect their sacred places. But nothing, absolutely nothing in the landscape would indicate that it was a sacred site.

*

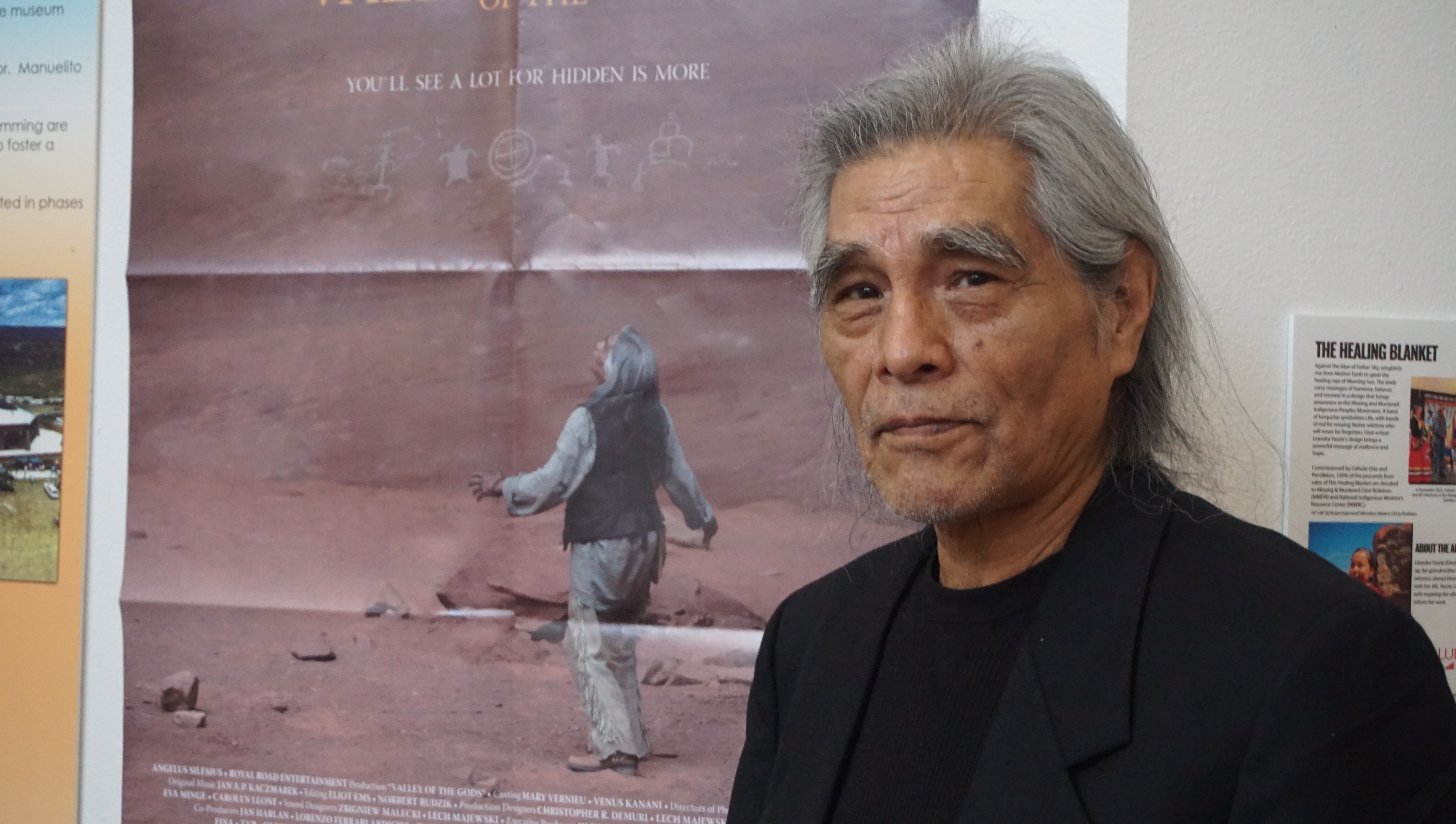

Discussions about cultural appropriation belong to our time. Also here in Window Rock. Tony Hillerman is the reason. His Navajo crime novels are available everywhere. The only problem: Hillerman was a white man. Is it a problem at all? No, says Joe Runninghorse, an actor from Santo Domingo Pueblo, who appears at the festival in the feature film “Valley of the Gods” by Polish director Lech Majewski. Joe is one of those people who change the atmosphere of a room just by appearing. Joe has a role in “Dark Winds,” a successful TV series based on Hillerman’s novels which is now being continued by his daughter Anne. “Dark Winds” is the largest indigenous film production ever developed on Indian land. The only white people on the team are Anne Hillerman – and Robert Redford, who is producing the whole thing.

Oh, I just used the term Indian. No problem, I’ll take the shitstorm from people in Germany. I’ve become a bit sensitive about this subject. Here’s an anecdote. This is a scene from a shopping area in Düsseldorf: an information stand for Leonard Peltier, signatures are being collected for the “Indian political prisoner.” She won’t sign, a woman passing by says loudly, claiming “Indian” is discriminatory. And what does Peltier say in a poem from his book Prison Writings: My Life is my Sundance? “I am the Indian Voice.”

Replacing the term “Indians” with “indigenous people” may be politically correct in part, but the transition is far from complete. The indigenous peoples of the world all have a name. Only when these names are used and spelled correctly can we talk about political correctness. These peoples stand in the way of our plundering lifestyle, so it is less irritating to our consumer culture, to dismiss them with the umbrella term Indigenous. Those without a face are easier to exploit.

From Window Rock to Santa Fe, Eda is back at the wheel. The Museum of Contemporary Arts of the Institute of American Indian Arts is always worth a visit. A friendly young man sells the tickets; he comes from one of the pueblos north of Santa Fe. A tourist from Germany tries to ingratiate herself. She says to him that she has only just realized that Hillerman is not indigenous and she stopped reading immediately, only indigenous authors have the right to write indigenous crime novels in her eyes. “Yeah”, said the friendly Pueblo man, “we do have good authors too.” I don’t feel like interfering. When the tourist is out of earshot, I talk about the film festival in Window Rock and mention the “Dark Winds” series. “Yeah,” says the pueblo man, “Hillerman did a lot of good.”

Is it cultural appropriation or cultural appreciation at issue here? I would like to discuss this with Jill Momaday. Her father, the renown Kiowa writer N. Scott Momaday, passed away a few weeks ago. Scott was a friend, teacher, role model and guide. Jill can’t meet me. A man was shot dead in the street and the perpetrator has not yet been caught. She is not allowed by the police to leave her house. This is Santa Fe, too; the Wild West has made it to post-modern times. Jill and I speak on the phone. But the subject of exploitation remains untouched. We talk about grief and we talk about her daughter Natachee, who is following in her grandfather’s footsteps with her poetry collection “Silver Box.”. Moccasin footsteps. The critics are enthusiastic. I buy the poetry book and I am, too.

The black journalist Greg Tate, who used to write for the New York Village Voice, published the pamphlet “Everything but the Burden: What White People Are Taking from Black Culture” in 2003. The cover of the book shows a man from behind, below the belt. The pants are hanging low, it doesn’t get any lower. Among African Americans, it was a sign of solidarity with their imprisoned brothers and comrades-in-arms. In prison, belts have to be handed in and suspenders are not allowed. Then suddenly saggy pants appeared in the stores;, sniffed out and promoted by the fashion labels. With profit comes appropriation. And this is where Greg Tate comes in: Music, painting, cooking recipes, fashion, architecture … everything is exploited for profit under capitalism. Everything but the burden: exotic people are allowed to keep their struggle.

Everything but the burden. Post-colonial action requires us to question our lifestyle. And for us consumers to get involved! Hardly any of the raw materials that our way of life needs on a daily basis are available to us. Everything is preceded by a plundering foray. Of course, this can’t or won’t be heard so clearly – our language of consumption knows no raw terms for such truth.

Before the I-word, – Indian or Indigenous – it was about the N-word. Earlier literature contains “negro” or “nigger” as an acceptable description. Not so much anymore, particularly used by contemporary white writers. Publishers are bending, sensitive to critiques these N-words evoke in light of the racist treatment of Black people historically. At the same time, a legal movement flourishes to erase that history, changing laws, cleansing school curricula, banning books in public libraries, because it makes some – white – people uncomfortable. One could argue, in the alternative: How would erasing the N-word help in the slightest the black African population, let’s say around the uranium mines in Niger, if works by William Faulkner, Wolfgang Koeppen or Astrid Lindgren were cleansed of the N-word. Everything but the burden.

My friend Robert Hültner insists on using the word ‘gypsy’ in a novel. No French Gitan would consider it an insult – it is, like ‘Gypsie’, a corruption of ‘Egyptian’, as it was wrongly assumed in the late Middle Ages that this ethnic group was of Egyptian origin.

Robert told me about a Sinti whom he met at a Sinti-Roma workshop organized by Bayerischer Rundfunk in the city of Straubing. The Sinti said to him: “I won’t let anyone rob me of the word ‘gypsy’. In the past, it was simply a term for the travelling people, and there were fanciful and romanticized images of the ‘gypsy baron’, the ‘gypsy princess’, ‘gypsy music’ and so on. The Nazis covered this word with their filth and derived it from the word ‘travelling crook’. If we allow ‘gypsy’ to still be considered a dirty word today, then the Nazis have won.”

I kept the commentary by Roman Bucheli in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung from April 17, 2023: ” The new inquisition turns one’s own sensitivity into an instrument of power. The world doesn’t need to get better as long as nothing offensive, hurtful or irritating disturbs its own circles. The desired eradication of the N-word is therefore merely the symptom of an egocentric tendency, at the end of which the peace of the grave of self-sufficiency prevails.”

*

Before continuing my journey to the east coast, I visit Godfrey Reggio’s studio opposite Santa Fe’s once famous Cloud Cliff Cafe & Bakery ; Cloud Cliff baker Willem Malten accompanies me. Godfrey, who created the experimental film trilogy “Koyanisquatsi”, “Powaquatsi” and “Naqoyqatsi” forty years ago, is 84 years old. Dressed all in black, he awaits us, swaying to classical music, his beard flowing, a tight woolen cap down to his eyebrows. Over two meters high, he could be Albus Dumbledore, the grey eminence of Hogwarts. We are given a private screening of his latest opus “Once Within a Time,” an exuberant spectacle about our civilization. And immediately afterwards: “The Making of….” An unparalleled insight: a team in the flow of ingenious inspiration with a touch of magic. Godfrey, the magician!

At last, New York City. I’m walking around Manhattan with Alfred Meyer, a member of PSR (Physicians for Social Responsibility), a fellow anti-nuke campaigner my age. At Grand Central Station, the smell of a bakery catches me. I veer off course to the subway and follow my nose, Alfred at my heels. Cinnamon rolls with raisins! He insists on paying. “Can I get you anything else?” asks the young, smiling black woman behind the counter. “Yes”, says Alfred, “world peace”. Her eyes grow wide: “I wish I could help you,” she says.

“Democracy Now! The war and peace report”: Part of New York City for me. What a privilege to be able to tap into a credible news source. DemocracyNow!, presented by Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzales, reports from Monday to Friday on reality in all its absurdity: The USA delivers bombs to Israel and drops food for the Palestinians being bombarded by those weapons. Gaza dominates. And divides. After the Hamas terrorist attack on October 7, arms industry stocks are booming. Violence against violence. Anyone who criticizes Israel’s government runs the risk of being deemed anti-Semitic. Anyone who raises the historical context of the founding of Israel does, too. Why can’t we see the suffering on both sides? Why does the guilt of the Holocaust force us in Germany to be loyal to a regime that we abhor? We are supplying the Netanyahu government with the weapons it wants. Are we not thereby loading ourselves with new guilt?

*

Benjamin Netanyahu, Vladimir Putin, Erdogan, Yahya Sinwar, Ismail Haniya … the gallery of despots is never empty.: Driven by greed for power, hatred, megalomania. Blind, deaf, unapproachable, without scruples. The Indigenous world also knows one of these: Tadodaho – his story never fails to impress me.

It was around 1000 years ago, east of the Great Lakes, where the state of New York stretches out today. Tadodaho was a monster. The story describes him as a bloodthirsty sorcerer, writhing with hatred, snakes growing out of his head, dreadlocks probably, his penis so long that he wrapped it around his neck; he could call the winds and bring storms to a halt. A cruel society flourished around him, held together by fear and rampant cannibalism. They who killed each other were related to each other; they belonged to five tribes: Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga, Seneca.

In this darkness of fear, a figure of light appeared who is now referred to in the stories as the Peacemaker. The Peacemaker propagated a society in which women and men work together as equals and complement each other, in which the well-being of future generations must be the guiding principle of all political action. When he knew he had the majority of the population behind him, he and his followers marched towards Tadodaho. This part of the story is amazing! They combed him, they cleaned his eyes, his ears, they massaged him until the man became visible again, because he had been born as a human being.

The Peacemaker exposed the roots of a pine tree and called all the war chiefs to him and asked them to place their weapons under the roots; then he heaped earth over the weapons. We still refer to this act today when we talk about “burying the hatchet.” He called his proposal for coexistence the “Great Law of Peace.” It was the constitution that the Haudenosaunee still follow today. What impresses me so much is the adherence to the assumption that monsters also once came into the world as helpless human beings looking for affection and protection. The search for the disappointed, betrayed inner self, the human core – an unparalleled therapy.

The Peacemaker had saved the monster for his last move: He made him the guardian of peace. With one condition: All those who would follow him would bear his name: Tadodaho. So that people do not forget that peace is not the absence of war, but requires daily, active influence. And: we can all become monsters if we forget who we are. The Haudenosaunee’s current Tadodaho is Sid Hill, an Onondaga.

We need independent peacemakers. My wish is a daydream. A few days later I receive a message from the USA: On April 11, indigenous activists from all directions met for two days in Washington, DC “on the land where the Potomac River flows” for the First Global Summit on Indigenous Peacebuilding. The Haudenosaunee were represented. The Haudenosaunee are experts in war and peace and were asked to share their experiences of reconciliation. The question now is what will follow from the meeting on the Potomac River?

*

May has arrived. At the International Journalism Festival in Innsbruck, Austria, I meet journalist Ahmed Alnaouq, who comes from Gaza but now lives in London. His family, his relatives: recently killed. He won’t give up, he calls journalism the force without which a society is not free. And he asks us all: why do the powerful only react to violence? Would the unresolved conflict be of global importance to the media without the terror of both sides? It is May 5, Press Freedom Day. The next day, Netanyahu’s police clear the office of the international television station Al Jazeera.

In the three years of its existence, the festival has created a space that is second to none. Questions can be asked here that do not have to stand up to any kind of correctness. Journalist Giorgos Christides asks: “Greece hosts 35 million tourists every year – but 40,000 refugees are overwhelming the country?“

Window Rock is in front of me again, Klee Benally slips into my thoughts. I take a trip to YouTube and discover Klee. He is singing his cover version of the Simon Garfunkel hit “Sound of Silence.” On his guitar it says: “This Machine Kills Colonizers.” It’s a tribute to Woody Guthrie, who wrote on his banjo: “This Machine kills Fascists.” Take a look at Klee: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYu1jzL1jUw10

SHARE