01-09-2023

Tony Hillerman – a Case of Cultural Appreciation

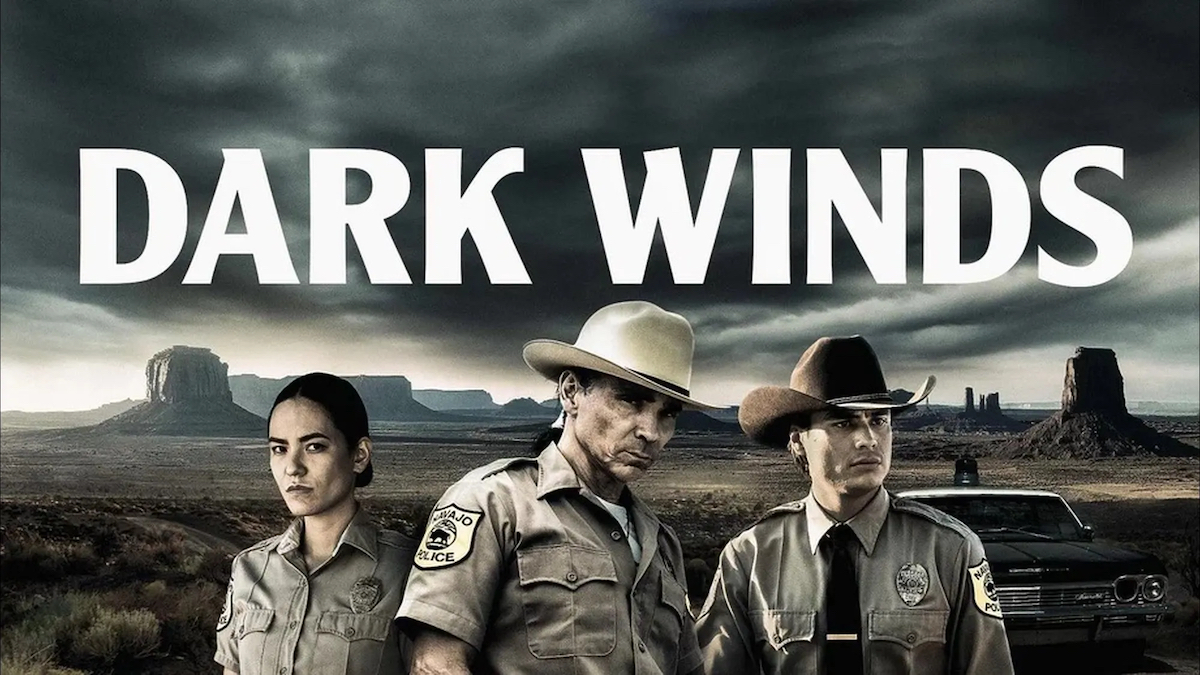

A classic comes back: Tony Hillerman's Navajo crime novels published by the Swiss Unionsverlag. A white author writing about people on an Indian reservation - is that still acceptable today? In response, a look at the online offerings of the most successful series: DARK WINDS has been running in the U.S. since June, and the series will be launched in German as WIND DES BÖSEN on September 12. The series is based on the novels by Tony Hillerman. Never before has a US film production had such a strong line-up of indigenous participants. Claus Biegert on Tony Hillerman.

By Claus Biegert

Tony Hillerman’s thrillers are set in a dual reality: in the Dinétah, the Diné settlement areas that today span the four U.S. states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona, and in the world outside the reservation boundaries, which in some novels extends as far as Washington and Los Angeles. Misunderstandings still occur on the threshold between these worlds; it was from this space of discrepancy that the author drew his plot lines, his suspense. He was interested in contrasting the unified image of the “natives”, which has been shaped by Hollywood clichés, with the precise rituals and values of the Diné. The Navajo speak of themselves as Diné, the people of men. Most self-designations of Native American peoples mean “human beings, real people, human people,” in distinction to the winged, four-legged, swimming, rooting peoples.

The author is a native of Oklahoma. As Anthony Grove Hillerman, he was born in 1925 at the former Mission Sacred Heart near the Potawatomi reservation. His father operated a general store and a tiny farm. There was no tractor or electric lights; the nearest library was thirty-five miles away. Oklahoma was Indian Country; it was where, a century earlier, those who stood in the way of white expansion had been “relocated” after President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act became law in 1830. In the way were the Choctaw, Chikasaw, Creel, Seminole, Cherokee, Shawnee, Ottawa, Sauk and Fox, Osage, Kickapoo, Wyandot, Ho-Chunks, Kaskakia, Peoria, Miami, Leni-Lenape, Illinois, Modoc, Oto, Ponca, Seneca, Cayuga, Tuskee, Quapaw – and the Potawatomi. Women and children died by the thousands in these “relocations.” Indigenous, Canadian-based writer Thomas King calls the tragedy a “Twin Tower Moment” in his work „The Inconvenient Indian“ (published in 2012).

Tony Hillerman’s environment was characterized by people who were refugees in their own country. He attended an off-reservation boarding school for Native American girls as a day student. “I was a one-man minority problem, and I’ve known since what it means to be a minority.” After graduating from high school, World War II followed; in Austria, he was wounded by a shell behind German lines. Initially blinded, he was soon able to see again; his right knee, however, remained damaged. He decided to become a journalist, graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 1946, and by the age of twenty-seven was already running the Santa Fe office of the United Press International news agency. He became editor of the New Mexican and lectured for many years at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque on ethics, literature and communication studies. In addition, he began writing novels. For Dance Place of the Dead, he received the prestigious “Edgar” from the Mystery Writers of America. After twelve volumes featuring Navajo policemen Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, the Navajo Tribal Council awarded him the title “Special Friend of the Diné,” an honor that no one else has received before or since. Hillerman died in 2008; he wrote eighteen Navajo novels.

On the Road with Tony Hillerman

Before the turn of the millennium, in 1991, I spent two days traveling with him and his wife, Marie, through Navajo and Hopi territories, whose villages sit on three mesas on their own reservation in the middle of Navajo territory.

Far to the west, in the motel next to the Trading Post of the settlement of Tuba City (which at that time had 8600 inhabitants), I witnessed waitresses lining up and asking for an autograph; in their hands they held up to five paperbacks.I had also witnessed his following elsewhere: At the annual meetings of the “Working Group on Indigenous Peoples” at the UN in Geneva in the 1980s, I came up against Tony Hillerman with a Navajo human rights activist. Her boyfriend, she told me with a laugh, had just started his job with the Navajo Tribal Police. “I gave him all the Hillermans so he would know how to behave.”

When I told Tony Hillerman this story, he was pleased; it loosened his tongue. We sat in the car. In front of us was the sand-colored backdrop of the Hopi mesas. He told us that his original intention was to create on the part of whites a sensitivity to the world of people on the foreign, Indian side, experienced as “exotic” on the reservations. “It’s always bothered me that Americans don’t care about the cultures in their neighborhoods, they have no idea what’s going on beyond the reservation boundaries.” How should he proceed? He started writing crime fiction that didn’t fit the familiar pattern, because his heroes weren’t from the white world. That sounds like extraterrestrials entering the scene, and it certainly came close to reality: the Diné reservation resembled another planet in the minds of many whites.

Another Planet?

Before the ninth manned lunar flight in 1971, the Navajo Nation Tribal Office in Window Rock, Arizona, received a call from Houston, Texas. It was NASA. They were preparing for the Apollo 15 mission and wanted to expose astronauts Jim Irwin and David Scott to as realistic an environment as possible in their new space suits and moon boots. The area in southwestern Arizona was similar to the lunar surface, the press secretary said, so whether they couldn’t do some kind of test walk on the reservation? Peter McDonald, then Tribal Chairman, loved the publicity and was excited. A space capsule was set up, and the men were in constant radio dialogue with Houston.

The astronauts in their spacesuits and oxygen helmets were doing a drill when a Navajo elder came along. He was a Yataalii, a medicine man. What was going on here, what these strange characters were up to, he wanted to know from McDonald. “These men are going to the moon next month,” McDonald said. “They’re rehearsing their landing with us.”

“Hmm, to the moon …,” mused the Yataalii. “Our legends tell us that we once traveled to the moon as well, on our way to the sun. However, we didn’t need such equipment – we used our minds. Who knows, maybe one of our own is still up there. I’d like to take a message back to the men.”

At the next coffee break, McDonald introduced the Yataalii to the Texas visitors and explained the facts. “Sure,” Irwin said, “we’re taking mail to the moon, too. If we run into any Navajo up there, we’ll deliver the letter.” There was only one problem with that, McDonald replied, Diné Bizaad was not a written language. “Then let him speak his message on tape!” Irvin retrieved a tape recorder and handed it to McDonald, who passed it to the medicine man.

That evening, Irvin inquired whether the Yataalii had been able to record the message. McDonald replied in the affirmative, playing the message and laughing. Irvin, of course, couldn’t understand anything, so Peter McDonald translated, “He says if these two strange characters want to make a treaty with you, don’t sign anything!”

In fact, the Navajo had long felt no need to be in exchange with the white outside world. Ever since they had been “relocated” by the U.S. Cavalry from their homeland in northeastern Arizona to Bosque Rodondo in eastern New Mexico in 1864 to 1866, they had harbored no desire for contact with whites. Hundreds had died on the Long Walk, and many hundreds later died in the barren area that was now to be their home. There was no firewood, hardly any food. After three years of crop failures, they demanded that President Ulysses Grant return them to their old land. In fact, a treaty was signed in 1868 guaranteeing their return. After the Long Walk back, they found their hogans – hexagonal, earth-roofed wooden houses – destroyed or burned, the orchards and cornfields destroyed, the wells poisoned, the sheep gone. It was a long time before they could resume their old rhythm of life.

Code Talkers for the US Army

World War II brought the two sides together unexpectedly. A Los Angeles city government engineer named Philip Johnston, who was a World War 1 veteran, suggested the U.S. Marine Corps use Navajo as a code. Johnston had grown up as the son of missionaries on the Navajo reservation and spoke fluent Diné Bizaad. His advice was followed. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, many young Navajo had enlisted in the military. Twenty-nine of them were selected as code talkers for the war in the Pacific. One was Peter McDonald, the Tribal Chairman mentioned earlier. By the end of the war, five hundred and forty Navajo were serving in the Marines, most as radio operators. This was more than one percent of the entire nation. Soldiers from other indigenous peoples were also called upon to cipher.

To this day, many apply for military service on reservations, as education and jobs remain scarce in many places, and alcohol and drug use proliferate in this vacuum-despite the now thirty-plus self-governing Native American colleges. In general, indigenous administrations lack the financial resources to build a self-governing infrastructure that aligns with their cultural values and promotes their own language. During the Vietnam War (1955-1975), many Navajo fought against the Viet Cong and also had to come to terms with the fact that they were killing people who were like them and – like they once were – defending their land against the U.S. military.

The high suicide rates among returning veterans soon sparked debates. The total number of Vietnam homecomers who ended their lives is believed to be more than 58,000. That figure exceeds the number of U.S. war dead. But the Native American share of this is surprisingly low in percentage terms.

The answer lies in culture. When a human being has killed another, he has destroyed the cosmic harmony. The Navajo call this harmony Hózhó (also Hozro), it is translated as “beauty”, it applies between all living beings, it is their connection to the universe. If it is out of balance, it must be brought back into balance. For this purpose, there are rituals to which all relatives are invited, because they belong to the Hózhó, which must be restored. War traumas require healing ceremonies; only they enable reintegration into society.

On his first visit to Window Rock, Tony Hillerman struck up a conversation with two men who had fought as Marines and code talkers in the Pacific War. For them, he learned, a Yataalii was called to perform the Enemy Way ceremony so they could once again “live in harmony with their people.” This meaning of ceremonies made a lasting impression on him; he wanted to bring it to his industrial, non-Indigenous society.

The response from the reservation gave him great satisfaction: when the students at St. Catherine Indian School voted him the most popular writer, or adults approached him and told him his books had reawakened their children’s interest in Diné culture. When a letter from a prison guard reached him, he knew he was on the right track with his novels. “Thanks to your books,” the warden wrote, “I now see the Indian prisoners with different eyes.” For changes of heart of this kind, the Navajo government had honored him, Hillerman the author.

Where did Hillerman get his knowledge? If we follow this question, we come across a way of working that shows decency and respect. He took his time when seeking Navajo families who would take a liking to what he was doing. He processed what he heard in his texts, came back, corrected when he made mistakes. He was always welcome, because what he reproduced was what he had been told. For his novel Speaking Gods, he visited Mae Thompson, who was known for her great cultural knowledge. When the book came out, she was accused by various Navajo of giving away too much spiritual information to a non-Diné. The Navajo Way, she responded, was so valuable that it needed to be shared with the world. “Our people revealed everything to him,” James Peshlakai, who served as Hillerman’s role model in Lamenting Wind, told an Associated Press reporter. “Our elders were happy to tell the stories they were never asked about by their children.”

Here, Peshlakai touched on a sore spot that affected many indigenous peoples of North America: the young generation’s lack of interest in their own culture during a long period of time.

I was able to witness this in the 1990s, when Hillerman was writing his novels, while filming on the Six Nations reserve in the Canadian province of Ontario. Cayuga historian Jake Thomas described to me how the knowledge of the Haudenosaunee (League of Nations of the Iroquois) had been handed down to him by his elders, knowledge that goes back almost a thousand years and can be “read” in graphic patterns and symbols on beaded belts called wampums. The Great Law of Peace, the constitution of the Haudenosaunee, is also recorded on wampums. It took four days to interpret the Great Law and “record” it orally for descendants. It always touches me when I watch the scene in my film Exit 16 – Onondaga Nation Territory: “Maybe it ends here,” Jake says there, “maybe it ends here.” He points to himself.

The Curse of Uranium

I also talked to Tony Hillerman about uranium. In the Navajo Nation, there is hardly a family that has not lost loved ones to cancer. The rituals of the Yataalii are powerless against radioactive radiation. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), there are 523 abandoned uranium mines on the reservation; “Clean Up the Mines,” an initiative of Navajo activists, estimates the number at more than 1,200. Navajo who were not educated about the radiation hazards worked in these mines. The high number of cancer victims led to the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in 1990 – after three decades of tough lobbying. To this day, the process of making amends has been tenacious. If the required paperwork is missing, the claim is forfeited; likewise, if the question about tobacco use is answered yes during an interview by government officials. Tobacco is considered a sacred plant and is used in ceremonies. The interviewees did not know that they were classified as smokers because of this.

Hillerman addressed uranium ore in his novel Dark Winds. I came to talk during our trip about the fact that the men who worked in uranium mills and during the day in the mines, breathing in radioactive dust, wore no protective clothing. “We were not warned either,” Tony says, “it was the time of nuclear euphoria.” He says that as a child, when he bought shoes, he had to keep putting his feet in an X-ray box to make sure the size was right. And suddenly I saw a scene in front of me that I had forgotten: Hertie department store in Munich. I look through a peephole at my feet, which are in Salamander shoes. I see my foot skeletons moving in the shoes and am fascinated, not wanting to stop trying them on. I was ten years old.

Appropriation or appreciation?

Even in the last century, the spark of a fierce debate ignited around the West’s hitherto unquestioned colonial past. It led to new valuations. Stolen objects and works of art from the South in museums in the North were now called stolen property, and their return was demanded. A new term made the rounds: cultural appropriation. This appropriation could also be observed in the fashion industry, in the media world, and in everyday life. The New York journalist Greg Tate brought the facts to a common denominator: “Everything But the Burden”. We in the dominant society take what we like from strangers, the persecuted, people of color, the underprivileged: music, patterns, fashion, art, ideas, recipes – “everything but the burden.” Not surprisingly, Tony Hillerman’s works have also been subjected to this test.

The English language distinguishes between Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Appreciation. In Tony Hillerman’s case, as this discussion reveals, it is appreciation. He acted as an ambassador for the Navajo and was seen as such by them. So it is not surprising that a large-scale TV series with several seasons has now been created from his novels: Dark Winds.

It was shot exclusively in Navajo Country in New Mexico, and the production center was the Camel Rock Film and TV Studio (a former casino) of the Tesuque Pueblo, north of Santa Fe. There had been film adaptations of his works before, but would Tony Hillerman have dreamed that an hour’s drive from Albuquerque, his home, a film series featuring his novel characters would one day be made with a predominantly indigenous crew? The five-person scriptwriting team included two Navajo, Chris Eyre (Cheyenne/Arapaho) directed, and the leads are Zahn McClarlan (Lakota) as Joe Leaphorn, Kiowa Gordon (Hualapai) as Jim Chee, Jessica Matten (Red River Metis-Cree) as Sergeant Bernadette Manuelito, Diana Ellison (Navajo) as Emma Leaphorn, Eugene Brave Rock (Kanai) as Yataalii Frank Nakai. The producers are Graham Roland (Chickasaw), George R. R. Martin, a longtime friend of Hillerman’s, and Robert Redford. Never before has a film production of this size (production cost per episode: five million U.S. dollars) had an indigenous workforce of 85 percent. Tony Hillerman would have been pleased to see that, since its launch, the series has been one of the most successful in the country whose view of itself he wanted to change with his novels.

SHARE